5. FUSTE OPINION AND ERRORS

Fuste Opinion Page: 1-18

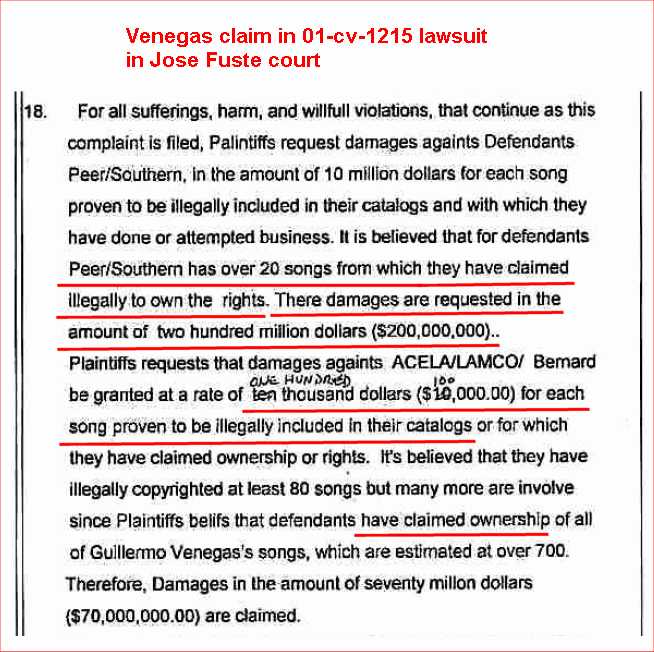

Fuste text: Plaintiffs request monetary

and injunctive relief

Error: Fuste did not mention or give or

deny any injunctive relief. So he forgot about

it?

See page 77, line

15 for more re injunctive relief

Fuste Opinion Page :

2-21

Fuste text: Since GVL’s death, the rights

to GVL’s music have been in dispute between

Plaintiffs and Defendant Chávez-Butler in the

Puerto Rico state courts.

Error: Not so. The dispute referenced

ended in 2002. This comments by Fuste helps Peer

position that the music was in dispute and that

somehow prevented them from making royalty payments

never made to plaintiffs and that would mean that

Peer dd not have to say "Peer did not pay royalties

because the songs belonged to plaintiff which is why

Peer

asked

for their assignments in 1997" .

Fuste Opinion Page:

2-7

Fuste text: Peer Defendants then

report and pay royalties to the composers in

connection with their licensing activities

Error: But this case showed the opposite,

that Peer does not pay royalties. This comment

wrongly helps Peer image. Again Fuste takes Peer

words at face value without any proof and the

repeats them.

Fuste Opinion Page:

3-3

Fuste text:On September 22, 1999, the

state trial court issued its opinion, finding that

GVL’s musical work belonged to his children.

Error: 1. The real date is January 28,

2000 at the Appeals court. It is a mystery whay the

date of January 28, 2000 appears nowhere. It was

hidden, really.

Error: 2. On another opinion, by Fuste,

Fuste stated that the PR courts declared themselvers

without jusrisdiction as to copyright claim.

Error: 3. The statement contradicts a

prior "renewal rights" ownership decision by the

judge, that there are other owners as well.

Error: 4. On the prior "renewal rights"

ownership decision judge Fuste states that the the

state trial court did not decide about ownership of

(already existing) renewal rights, even though the

state courts stated that "ALL rights" belonged to

plaintiffs. Since ALL means all, judge Fuste was

wrong in assigning renewal rights to LAMCO parties

in his decision.

Error: 5. The prior "renewal rights"

ownership decision by judge Fuste decision means

that the children of GVL had to argue their

ownership rights twice, once in state courts and

then in federal court, all because in the state

court the suing party (hered defendant Chavez) did

not argue or adequately argue or bring up an alleged

right to renewal rights. Because the children of GVL

had to litigate the same claim by Chavez twice, that

is clear a violation of the res judicata principle

that a single controersy must be resolved in a

single case and not multiple cases. On this Fuste

made a major error.

Very strange: The date of January

28, 2000, where the Puerto Rico court stated that

all rights belonged to the children of Venegas and

that if Chavez had any rights she expressly ceded

them to the children. That was appealed by Chavez.

Fuste ignored the decision of January 28

ignored the appeal to favor ACEMLA.

Very strange: While LAMCO parties

claimed that they had renewal rights on some

songs, they made no such claim for termination

rights. Fuste awarded 20 percent on 8 renewal

songs, but failed to award termination rights to

LAMCO parties and they would have been a 50

percent share in 21 songs. Well not so strange

after all. By giving LAMCO parties 20 percent on 8

songs, that means that less rights belong to

plaintiffs, GVL heirs, whereas if termination

rights had been awarded to LAMCO parties, those

rights would have meant less rights for Peermusic.

Note: In march 7, 1997 GVL estate

executrix Chavez Butler (now part of LAMCO

parties) tried to terminate the songs with Peer.

Peermusic should have at least told her the dates

when termination rights accrued under their

theories. Instead Peermusic never replied to

Chavez Butler, apparently applying to her also the

Slonick-Peermusi theory that GVL heirs had no

right to information. It is very strange how Fuste

decided about LAMCO party rights and that LAMCO

parties did not object the leaving out of

termination rights.

Note: By owning 20 percent of a song

(the estate executor Chavez) as decreed by

Fuste, when that 20 percent owner previously stole

over 500 songs from the GVL heirs (owners of the

80 percent) and on top of that sued the same GVL

and on top of that exploited the song (over

$60,000 income) without sharing any of the income

with the other owners, the arrangement has a

significant meaning overlooked (another error) by

Fuste: The song is unexploitable since to exploy

the song collaboration and payments of income

between all owners is required. That means that

Genesis is is unexploitable, commercially

worthless, a total loss, since the GVL heirs could

not even enforce their rights since to do that,

any claim in court must represent 100 percent of

the ownership and that cannot be achieved if there

is no trust among the varios owners. This result

is contrary to the constitutional intent of the

copyright law, to promote the creation of works of

art. Who will create art knowing that the art

could end up dead because of court decisions (and

because the law forces the creation of multiple

owners), like in the present case.

Fuste Opinion Page: 3-18

Fuste text: Plaintiffs alleged that GVL

never assigned any rights to Peer Defendants.

Error: Plaintiffs never alleged any such

thing. There was not doubt that GVL signed some

contracts but the problem Peer has was that before

this trial it never presented to plaintiffs the

evidence they had and in effect gave up the

ownership they may have rightfully had and decided

to recognize

plaintiff as owners in 1997 (see Fuste comment)

when it requested new assignments. Fuste says this,

out of his own volition to make look bad when

associated with the sentence that the songs were

assigned to Peer and that that assignment is still

in effect. This should not happen (look bad) because

by 1997 (see

Fuste comment) , when Peer requested

assignments to all Peer (now) claimed songs Peer

could not or would not show or had shown any

assignment document other than a blanket assignment

(1952 contract) that was summarily rejected as

worthless by plaintiffs, GVL children.

Clearly, plaintiffs had every right to state that

GVL had never assigned any song to Peer.

Note: The assignment request by Peer was

spoken of at trial by Rafael Venegas and the

assignment request documents are part of plaintiff

exhibits.

See

Peer

assignment request in 1997

See

ownership interruption

Fuste error re GVL music case at Arecibo

court

Fuste Opinion Page: 3-5

Fuste text: The state trial court also

concluded that it had no jurisdiction over

Plaintiffs’ copyright claims.

Error: This is a totally wrong

interpretation of what the PR courts decided.

The court decided in favor of the copyright claims

of the children of GVL, after Chavez claimed (in two

Certiorari) that the court erred and that she

had federal renewal rights and that the court had no

jurisdiction. The PR courts stated that the it did

had jurisdiction and rejecterd her renewak

rights/federal law claims. What the PR court

rejected was a counter suit claim by the children of

GVL because it lacked jurisdiction - the claim

looked like a copyright infringement claim and the

court interpreted it as such and said such

infringement claims are a federal issue. But now

Fuste is saying there was no copyright infringement

in the transfer of non existing rights (for the

estate-executor) by estate-executor to ACEMLA and

the subsequent licensing except for the one song

(Genesis) payment by Banco Popular. A clear conflict

between courts. Fuste is also wrong about the

transfer by the estate-executor as follows: The

estate-executor authorized ACEMLA to license the

songs and ACEMLA did license songs to Sonolux (a

direct infringer) which in turn produced records.

Therefore the estate-executor authorization to

ACEMLA was an act of (contributory) copyright

infringement for these songs licensed by ACEMLA:

Genesis, Desde que te marchaste, No me digan

cobarde, *Amargo amor, *Chiquita, *Be my love, *El

angustiao, *Lost, Maria, *Nuestro Amor, *Pain of

Love, *Verano sin amor, voy asi, and other

miscellaneous licenses which ACEMLA (as vicarious

infringer) issued.

Because of this interpretation of what

was decided in state trial court, Fuste gave

himself the liberty of deciding the ownership fate

of 8 (renewal period) songs in favor of Chavez by

ignoring the fact that Chavez had claimed

federal law rights and that claim was rejected

by the Puerto Rico Supreme Court and that was

final for all courts unless appealed to the US

Supreme court. As it turned out the appeal was

made to Fuste by ACEMLA (who has no right to get

involved in Chave's possible rights) who made the

wrong decision that "The state trial

court also concluded that it had no jurisdiction

over Plaintiffs’ copyright claims"

By deciding that Chavez had rights in

8 renewal period songs, after Puerto rico courts

had decided she had no such rights, Fuste

violated the Rooker-Feldman

doctrine, that says federal courts cannot review

what has been decided in state couert.

Fuste Opinion Page: 3-16

Fuste text: The complaint alleges that

Peer and LAMCO Defendants infringed the copyrights

in unspecified musical compositions ostensibly

written by GVL and owned by Plaintiffs.

Error: "Ostensibly" applies only to the

songs that Peer claims to own, because for some Peer

has no score or lyrics,

Fuste Opinion Page: 3-18

Plaintiffs

alleged that GVL never assigned any rights to Peer

Defendants.

Error:

Plaintiffs never alleged such a thing. This "fact" was

made up by the judge. What plaintiffs said to the

court was that before the lawsuit Peer refused

to show the documents that proved such assignments and

that in 1997, rather than show the proof of the

assignments, Peer acknowledged plaintiffs as owners

and made an offer to administer the songs in exchange

for assignments from plaintiffs for all songs. The

offer was rejected by plaintiffs.

Fuste Opinion Page: 3-22

Fuste text: Plaintiffs claim copyright

ownership by virtue of a copyright registration

certificate filed by Rafael Venegas in the United

States Copyright Office on October 23, 2000,

Error: Not so. Ownership is claimed by

virtue of Puerto Rico inheritance laws and Copyright

law.

Fuste Opinion Page: 4-3

Fuste text: The ownership of eight

copyrights in their renewal terms after 3 GVL’s

death remain unsettled between Defendant

Chávez-Butler and Plaintiffs.

Error: In other parts of the opinion Fuste

says that LAMCO parties have rights. Opinion: In

light of PR inheritance law requirement of exclusive

inheritance this issue will have to be resolved.

Fuste Opinion Page: 4

Fuste text: GVL signed ten contracts with

Peer Defendants

Error: Only three were presented by

Peer (1947-1952-1970) and they may be falsified

because of the Peer habit of requesting signatures

on blank

contracts - some of which were presented at

trial. The MAS ALLA contract of 1947 is suspect

because Peer knows nothing of the song or documents

about were not presented in discovery perhaps to

hide something about the song. Judicial perversion

of the truth.

Fuste Opinion Page: 4-13

Fuste text: In all, GVL signed ten

contracts with Peer Defendants for the rights to his

songs.

Error: This is false. At most GVL signed

three song assignment contracts with Peer.

What Fuste has done is that he has added the seven non exclusive

and unworkable song assignment contracts that

GVL signed with PHAM, a Mexican publisher that

surely never divulged to GVL that it had a

contractual co-publisher agreement with Peer or that

they belonged to Peer (as Peer now claims). Peer

used the assignment of seven songs through seven non exclusive

and unworkable contacts to PHAM in 1969 as

proof that GVL was satisfied with the non existent

Peer performance. Peer never got a single GVL song

recorded in over 50 years it allegedly administered

21 GVL songs.

Note: If PHAM assigned the rights to the

song to Peer, that is to their parent company, who

wound up retaining 87 percent of the royalties on

the fist royalty cut, this was not in the interest

of GVL. In GVL's best interest, PHAM had to find

co-publishers that actually promoted the use of

the songs at the lowest cost, no a publishers like

Peer who did no promotion at all and retained 87

percent of the royalties. An insider conspiracy

against GVL but Peer owned PHAM? As ordered by

Peer? We shall find out soon enough.

Fuste Opinion Page: 6

Fuste text: Peer Defendants agreed to

“make reasonable efforts to publish or exploit

certain of the musical compositions...

Error: Fuste never makes a determination

as to whether that effort was reasonable. The

evidence is that Peer never got anyone to make a new

recording of any of the songs GVL may have assigned

to Peer.

Fuste Opinion Page: 6

Fuste text: Under GVL’s signature, there

is an additional clause, in different typeset, which

states in quotation

marks, that “[a]fter the expiration date,

this contract will continue in full force until all

moneys advanced are recovered.”

Error: The legality of this fact is not

further discussed.

Fuste Opinion Page: 6-7

Fuste text: Peer Defendants agreed to

“make reasonable efforts to publish or exploit

certain of the musical compositions composed and

written by [GVL],” and to pay royalties of, inter

alia, fifty percent of the net amount received for

mechanical royalties, synchronizing fees,

transcription fees, foreign royalties, and

performing fees.

Error: The Peer-GVL contract of 1952 says

no such thing. Per that contract Peer agreed to

nothing. All that it says is that Peer MAY exploit

certain songs. The word MAY means they do not have

to perform anything at all. Anyway the net result of

whatever reasonable effort was made is that not a

single new recording has been license by Peer

probable since the contracts was signed in 1952 and

certainly no recording has been made since 1954

(This is the year I migrated to New York) and all

recording of those songs were made before or

licensed by another (GVL himself or ACEMLA). PHAM songs excluded

from this comment.

Fuste Opinion Page 7-1

Fuste text:GVL contacted Peer Defendants

in 1964 to obtain a release from Peer’s construction

of the 1952 Agreement.

Error: There was no evidence, other than

heresay or documents not signed by GVL, that what

Fuste says is true. The truth, as evidenced by

Peer's documents, is that GVL contacted and combated

Peer several times to get his songs back starting in

about 1953. Reason: GVL realized from the beginning

that Peer was not promoting the songs he gave

(unknown at this time, since Peer kept no records -

or destroyed them - of songs received) ) and royalty

payments were not being received.

Error: Fuste could have said, more

accurately, that "Peer Defendants developed a plan

in 1964 to have GVL return unrecuperated royalty

money to Peer and to to get the assignments to a

number of songs that Peer planned to get anyway

"without the author suspecting".

The basis of the Fuste comment is

a 1964 letter

that was not shown or copied or even mentioned by

Peer to GVL heirs before the lawsuit was filed.

Because of this the letter is inadmissible as

evidence. The fact that the letter was never

shown to heirs meant that heirs did not know when

any song named in the letter was assigned so as to

determine when the assignments could be

terminated by the heirs so as to regain

their control as allowed by law.

"GVL to Peer" Letter: Page 1

Page

2

Notes:

The letter was actually made by Peer, so

it is a Peer to GVL letter.

If GVL had refused to signed this

letter, the songs would be stolen by Peer anyway

per the "without

the

author suspecting" plan.

Also the letter was never recorded by

Peer as required by the copyright law

then in effect.

In essence, by not signing the agreement

and forwarding a signed copy to the composer, Peer

aquired no responsibility to the composer to

exploit the songs for his benefit.

The 1964

Letter

of Agreement

Fuste Opinion Page: 7-3

Fuste text: Further, on April 29, 1964,

GVL sent a letter to Peer Defendants

Error: This is not true, it is a

fabrication, as GVL did not send any letter to Peer.

GVL was given a page 2 of a two page letter to sign.

This letter included a common contract trick: You

sign and Peer will give you a copy of the Peer

signed version and that version would never be given

to the composer. Thereafter composers do not know

what they signed and if they go for legal advise to

a lawyer they cannot get it because the need a copy

of the contract, just as happened to us, where Peer

stonewalled in providing contracts. This letter was

written by Peer at the same time it was trying to

acquire songs "without the composer suspecting".

Also the letter is not signed by Peer (as is

required by the letter itself to make the tems of

the letter valid) and that makes the letter invalid

to make any claims by either party.

The letter has two pages. All the

contract terms are on the first page. The

signature is on page 2, the page that basically

says nothing material. Since the two page letter

fitted easily on one page it is clear that the

idea was to have the ability to change page one

and replace it with a new one, with terms and

conditions that the signer of the letter never

saw. This explains why GVL seems to certify the he

composed the song BORRACHO SENTIMENTAL and

assigned the song to Peer on page one, a song that

GVL clearly did not composed. GVL wrote to Peer

about this when he found out that Peer had put his

name on the song BORRACHO SENTIMENTAL.

Note: Fuste took gave credence to this

letter and it is based on it that he gave Peer the

rights to many songs. Had he not done so Peer

would have had to pay many millions of dollars in

damages to plaintiffs. Fuste took five months to

decide that this letter was legitimate, a clear

error that saved Peer perhaps over $50,000,000

(fifty million dollars).

Note: Between the 1952 contract and this

1964 letter Peer did not have a single song

recorded (at least no evidence of such a recording

has ever been seen by plaintiffs. A contemporary

Peer letter indicates that GVL claimed that Peer

had done nothing with his songs. If GVL had

the option of not making this 1964 "assignment"

why would GVL have done so in view of Peer history

of non performance of the contract and its utter

failure to have one single song recorded? Sounds

wierd, doesn't it. The only explanation: The

letter is a forgery - page one was switched. After

all Peer was in an "without the author

suspecting" mode of operation. After this

letter was dated, Peer never got any of the songs

recorded, in over 40 years. Some are really great

songs.

Note: The letter in question is invalid

because it it not signed by Peer. Also Peer

presented no evidence that a signed copy was ever

forwarded to GVL. Clearly for this letter to be

considered a contract a Peer signed copy must have

existed and forwarded to GVL. Otherwise GVL could

not make any contractual claims against Peer.

The basis of the Fuste comment is

a 1964 letter

that was not shown or copied or even mentioned by

Peer to GVL heirs before the lawsuit was filed.

Because of this the letter is inadmissible as

evidence.

"GVL to Peer" Letter: Page 1

Page

2

Note: The letter was actually made by

Peer, so it is a Peer to GVL letter.

If GVL had refused to signed this

letter, the songs would be stolen by Peer anyway

per the "without

the

author suspecting" plan.

Also the letter was never recorded by

Peer as required by the copyright law

then in effect.

In essence, by not signing the agreement

and forwarding a signed copy to the composer, Peer

aquired no responsibility to the composer to

exploit the songs for his benefit.

Note: For

the 1952 GVL-Peer contract to be modified through

the 1964 letter of agreement cited by Fuste, there

had to be additional considerarion (payment to GVL)

for it to be effective (valid). But instead of

having additional consideration, the agreement

required GVL had to return money to Peer, the

opposite of additional consideration.

Fuste Opinion Page: 7

Fuste text: states that the

compositions were written by GVL

Error: Since it include at least a song

not written by GVL, that is proof that this letter

(at leas page 1) is fake.

Fusté on alleged 1964 assignment

letter

Fuste Opinion Page: 7

Fuste text: I hereby certify that the

above list of musical compositions is complete and

accurate

Error: It could not be accurate if it

included a song GVL did not write (Borracho Sentimental).

Of course it could be argued that maybe GVL was not

accurate, but this letter was written at the same

time or thereabout when n the request was made by

Peer to its Puerto Rico manages to acquire songs

"without the author suspecting.

Error: Fuste awarde the song Borracho Sentimental

to Peermusic without due process

for the real owner.

By decreeing that Borracho Sentimental

belongs to Peer that will have the effect that a

recording may be produced in the future with the

song identified as a GVL song, a moral rights

violation against plaintiffs caused directly by

Fuste.

Suspect that this Fuste decree re Borracho Sentimental

is meant to save Peer from the embarrassment of

Peer in its claim in Peer vs. LAMCO before Perez

Gimenenz.

The decree that songs belong to Peer are

wrong because Fuste has no proof that GVL wrote

any of the songs, the only valid proof being the

signature of GVL in a document with the song score

or lyrics. Just a signature on a list of songs

that include at least one non GVL song (Borracho

Sentimental) makes the GVL declaration (on 1964

letter written by Peer) that he wrote the songs

non valid, the only explanation being, since GVL

was not a thief, that: 1) page one was switched

by Peer after he signed the second page. 2)

GVL did not understand the letter because it

was in english.

Note: The

1964 letter on which Fuste based his decision, as if

the letter was a valid contract, is an

invalid document because it has no Peer signature

and the document itself states that without a Peer

signature the document is not valid. Also for a

contract to be valid, it must be signed by the two

parties. Fuste makes no mention of this in his

decision.

Note: The letter in question is

invalid because Peer did not presented any

evidence that a signed copy was ever forwarded to

GVL. Clearly for this letter to be considered a

contract a Peer signed copy must have existed and

forwarded to GVL. Otherwise GVL could not make any

contractual claims against Peer. Fuste

makes no mention of this in his decision.

"GVL to Peer" Letter: Page 1

Page

2

Note: The letter was actually made by

Peer, so it is a Peer to GVL letter.

In essence, by not signing the agreement

and forwarding a signed copy to the composer, Peer

aquired no responsibility to the composer to

exploit the songs for his benefit.

If GVL had refused to signed this

letter, the songs would be stolen by Peer anyway

per the "without

the

author suspecting" plan.

More here: Renewal

rights error.

Note: The letter of agreement was never

recorded by Peer as required by the 1909

Copyright Act

§ 30.Same; record

Every assignment of copyright shall be

recorded in the copyright office within three

calendar months after its execution in

the United States or within six calendar

months after its execution without the

limits of the United States, in default of which

it shall be void as against any

subsequent purchaser or mortgagee for a valuable

consideration, without notice, whose

assignment has been duly recorded.

Because the document was not recorded,

when the heirs of GVL did a search at the

Copyright Office before suing Peer, the letter of

agreement was not found. The purpose of the

required recordation at the Coyright Office was

precisely to put on notice that songs were

assigned by the author. See more on recordation

requirement here.

Fuste Opinion Page:

8-3

Fuste text: ....in accordance with the

terms and provisions of my aforesaid agreement with

you.

Error: This section cites the

contetnt of a letter but intentionally and

deceitfully leaves out the following text: "Your

signature at the bottom will signify your

accepatance of and agreement of all the terms and

conditions set forth in tis agreement." The agreement was never signed and

accepted by Peer.

See copy of agreement: "GVL to

Peer" Letter: Page 1

Page

2

Note: The letter was actually made by

Peer, so it is a Peer to GVL letter.

If GVL had refused to signed this

letter, the songs would be stolen by Peer anyway

per the "without

the

author suspecting" plan.

Fuste Opinion Page: 8-19

Fuste text: Each agreement provided for a

territorial exclusion of Puerto Rico, which would

allow GVL to license his work in Puerto Rico.

Error: Shows Fuste bias, Should have said

that prevented PHAM,

the copyright owner or its licensees (Peer / ASCAP /

Harry Fox) from licensing Puerto Rico firms or

licensing products to be sold in Puerto Rico.

Fuste Opinion Page: 8-14

Fuste text: a) a Mexican music publisher

that, at the time, was owned by Peer. b) PHAM is no longer owned

by Peer Defendants.

Error: Fuste assumes that Peer that Peer

facts are correct, but Peer has never

presented proof they ever owned or founded PHAM.

Information on the Internet suggests that PHAM has

always belonged to Grupo Televisa S.A. or its

founder, PHAM founder Emilio Azcárraga

Vidaurreta (1895-1972). At trial Peer said they

founded PHAM.

Fuste Opinion Page: 9 footnote

Fuste text: PHAM obligates Peer to account

and pay royalties to PHAM,

not to the writers who have contracted with PHAM

Error: a. Plaintiffs asked Peer to account

for illegally collected royalties in PR. They never

did. Interestingly Fuste does not even ask Peer to

return that money nor doe he mention that that issue

is to be resolved in another case before Perez

Gimenez.

b. But Peer tried to get rights to PHAM songs from Venegas

heirs in 1997 and they could only be acting as agent

of PHAM. So Peer was an agent forgetting the rights

to song but not for accounting for the illegal

royalties collected from Banco Popular. This is

fishy and/or wrong.

Fuste Opinion Page: 9-11

Fuste text: Peer Defendants do not know

whether PHAM paid the

amounts due to GVL as indicated in Peer Defendants’

statements to PHAM.

Error: Not interested ? Nice partnership.

One partner (Peer) doesn't care if the other partner

(PHAM) is a thief and Fuste swallowed this illogical

"fact" that Peer does not know if PHAM pays

royalties. Actually the Peer statement was perjury

because various Peer persons were informed by Rafael

Venegas that PHAM was not reporting or paying

royalties to GVL heirs.

Fuste Opinion Page:

9-13

Fusté text: In 1969, GVL signed a

series of single songwriter agreements with

Promotora Hispano Americana de Música (PHAM), a Mexican music

publisher that, at the time, was owned by Peer.

Error: Then there is double and triple

dipping, collecting royalties fist in the USA or

another Peer sub publisher and making a cut (there

were cuts of 87.5 percent made by Peer on the Banco

Popular royalties before sending royalties to PHAM

who never reported the rest of the money to the

heirs of GVL.). This was not taken into account by

Fusté.

Error: Fusté assumes incorrectly

that whatever assignment GVL made to PHAM was valid.

It was not for several reasons:

a. The assignment contract was not signed

by an American consular representative as required

by American law. The contract was also not signed by

a Mexico Foreign Affairs official. Therefore the

assignment is ilegal under American law and may be

ilegal under Mexico law.

b. The contract was not recorded at the US

Copyright Office within two months (this is the

limit for recording the transfer of rights in a

foreign country such as Mexico) of the signature

date. The recording was made by Peermusic (for PHAM)

in 1999. 30 years after the fact. Thus, if after GVL

died, the heirs of GVL or anyone else wanted to know

if GVL has assigned right to Genesis, that

information was not available at the US Copyrigth

Office.

c. The GVL-PHAM contract does not state

how much consideration was paid to GVL for his

giving the rights to PHAM. Meaning, there was no

consideration specified in the contract, meaning the

song was obtained for nothing.

d. The contract stated that GVL retained

the rights for the Puerto Rico territory and for

copyright s the Puerto Rico territory and the

american territory are the same. Therefore, PHAM was

at best given a license, not exclusive ownership as

implied in the PHAM copyright.

e. Wen GVL signed the contract he was not

aware that Peer claimed to own PHAM and that Peer

had actually stolen his songs (see WITHOUT

THE AUTHOR SUSPECTING). GVL was aware that

Peer was an utter failure in getting his songs

recorded... see THE

INCREDIBLE VENEGAS SONG EARNINGS REPORT FOR ~50

YEARS (17 years by 1969).

e. At the time of the trial, GVL had died

10 years earlier. During those 10 years there is no

evidence that PHAM paid any royalties to the GVL

heirs. Additionally there was no evidence that PHAM

ever paid GVL any royalties. Those facts made

whatever assignment contract GVL had signed suspect

and no longer enforceable.

f. The contract says it was signed in

Mexico. GVL was not in Mexico at the time. At the

same time there is evidence that Peer was at the

time arranging a dinner for GVL under the pretense

that the host was a PHAM official, for the purpose

of getting an assignment of Genesis to PHAM.

Fuste Opinion Page: 9-20

Fuste text: Southern agreed to pay GVL a

$300.00 advance against royalties in consideration

for the 1

assignment.

Error: But GVL heirs were not informed of

this when Peer

requested

assignments in 1997 (see Fuste comment)

for this song.

Fuste Opinion Page: 10-7

Fuste text: Several songs owned by Peer

Defendants in their original term of copyright have

reverted to Plaintiffs and Defendant

Chávez-Butler in their renewal term

Error: The songs were if anything, owned

by PHAM, not Peer.

Fuste Opinion Page: 10-footnote-

Fuste Opinion Fuste text: Copyrights for

works created before 1978 persist for an original

term of twenty-eight years and...

Error: It omits that the work must have

been published.

Fuste Opinion Page: 10-footnote

Fuste text: but the assignment is valid

only if the author is alive at the start of the

renewal term

Error: It omits the fact that the

assignment of renewal rights require the signature

of the composer. By not signing the composer retains

the renewal rights regardless of what a contract

says.

Fuste Opinion Page: 10

Fuste text: take the risk that the rights

acquired may never vest in their assignors.

Error: This is demagoguery. Publishers

take no risks at all since all they do is minor

clerical work with the composition. Whoever made

this comments must think that music publisher makes

huge investments to promote the music they acquire.

Fuste Opinion Page: 10-footnote

Fuste text: 1985)(“[U]ntil the renewal

period arrives, the renewal rights are not vested in

anyone.

Error: This seem contradictory to saying

that renewal rights vested on Peer if GVL was alive

when renewal period arrived, as Fuste states

elsewhere.

Fuste Opinion Page: 11

Fuste text: GVL retained ownership of Alma

triste in Puerto Rico

Error: Then the ownership was split and

this goes against the indivisibility concept that

says that if ownership is shared between the

original owner and a publisher, all the publisher

has is a license, not ownership. This applies to all

PHAM songs.

Fuste Opinion Page: 13-5

Fuste text: Concierto para decirte

adiós was published on May 22, 1970.

Error: No evidence was presented regarding

this fact. Among the Peer documents the 7 PHAM songs

only one song had an indication that it may have

been publishes because publishing grade sheet music

was supplied by Peer (but no proof that sheet music

royalties had ever been paid or that copies were

actually sold) and it was Genesis. Yet for Genesis,

there is no publication date mentioned by Fuste.

Again Fuste takes for granted what appear on papers

(copyright registration in this case). Maybe Fuste

does not know that Publisher are reckless when

putting publication dates on copyright

registrations.

Fuste Opinion Page: 13-13

Fuste text: The renewal rights throughout

the United States, including Puerto Rico, arose on

January 1, 1998, and are owned by Plaintiffs and

LAMCO Parties.

Error: The renewal rights are for the U.S.

and all countries signatories of Berne treaty (who

are obliged to recognize U.S. rights). If this were

not so, all U.S. renewal rights are invalid for the

rest of the world and the music is in the public

domain, including those that belong to Peer, outside

the US. Here Fuste is playing a Peer card... that

Peer owns the rights outside the U.S. (regardless of

PHAM ownership, which

may be extinct by Mexican law anyway).

Fuste Opinion Page: 15 line 4

Fuste text: The renewal rights throughout

the United States, including Puerto Rico, arose on

January 1, 1999. The United States renewal rights

are owned by Plaintiffs and LAMCO Parties to which

Peer makes no claim of ownership.

Error: Fuste never makes a mention that

Peermusic never notified plaintiffs that hey had

acquired the renewal rights for the PHAM songs

without renewal registrations, HASTA QUE ME OIGA

DIOS, Primavera and Raza Negra or that it retained

rights for the rest of the world. When Peer tried to

obtain assignments from heirs in 1997 (see Fuste comment)

no mention was made that regardless of our

assignment Peer would have world rights. Deceit and

fraud by Peer.

See eternal

copyright claim by Peermusic

Fuste Opinion Page: 17-11

Fuste text: the above mentioned 11 1964

Agreement

Error: But the agreement was never signed

by Peer, so it is invalid by its own terms.

Fuste Opinion Page: 17-21

Fuste text: they were signed by Peer as

attorney-in-fact for GVL.

Error: But this is contrary to copyright

law that requires the actual signature of the

composer and Fuste does not mention that. Also Fuste

does not mention that if GVL gave Peermusic a power

of attornet back in 1952, that power was given

contrary to Puerto Rico (where the contract was

executed) law because it was not notarized and was

therefore illegal The issue was raised by plaintiffs

but that fact, which required a court decision) is

omitted altogether by Fuste.

Note: Everyone

or every government agencyt that requires a power of

attorney to allow a representation or a transaction

alwats says or refets to "notarized power of

attorney". Apparently Fuste does not know

that. For example, in New York, whose laws allegedly

apply to the GVL-Peer contract, for a transfer of an

automobile, to represent another in the transaction

a "notarized power of attorney" is

required.

To make

sure, the author asked this question by telephoneto

various Puerto Rico and New York State agencies: Is

there any chance that an unotarized power of

attorney have any valuee in the State of New York?

These were the replies:

Puerto Rico

Sate Department (787-723-4343) :None

Puerto Rico

Supreme Court-Notary (787-723-6033) : None.

Puerto Rico

Supreme Court-Notary Inspection (787-751-0457: None

New York

State Department (518) 474-0050): None.

Additionally

the renewal documents are signed with the name of

Guillermo Venegas alone and that makes it impossible

to determine who signed and if that was an officer

of Peer and if whoever signed was authorized by New

York state law. We believe that only these can sign

in New York: A corporate officer, partner, or member

or manager of a limited liability company and any

other signature is invalid.

The fact

that that the 1952 contract was not notarized meant

that GVL, who did not understand the language of the

contract (English) did not have the benefit of being

asked by the lawyer notarizing the document if he

understood the contract he was signing. In 1952 the

vast majority of Puertoricans did not understand the

English language.

Fuste Opinion Page: 18

Fuste text: Peer Defendants stopped paying

royalties in 1993

Error: Fuste does not use this information

at all, for example to increase damages for

statutory damages. Shows that Fuste is biased in

favor of Peer. Also the statment is not supported

through any document or evidence presented to the

court or to plaintiffs, that Peer paid up to 1993 or

that it made any royalty payments ever.

Fuste Opinion Page: 18-1

Fuste text: Peer Defendants stopped

issuing royalty reports in 1993 and did not provide

any royalty reports to Plaintiffs until discovery in

this litigation.

Error: Peer (or anyone else) did not

produce any evidence that they paid any royalties to

GVL on 1993 or any previous years. Fuste takes for

fact a Peer testimony which may not be true. It

semms that Fuste takes for granted anything that

Peer says but is nor supported by documents,

arbitrarily.

Note: Allegedly, on a separate case

being herd in Puerto Rico courts (2007, Ketty

Cabán vs. Peer) Peer has not been able to

produce proof (royalty checks signed by

Cabán) that they have made the royalty

payments they claim to have made to Cabán

because, allegedly, signed checks are not saved by

Peer (as allegedly required by law).

Fuste Opinion Page: 18-18

Fuste text: Peer had registered its claim

to Génesis

Error: Not so. The song was registered

with PHAM as owner. Again, Fuste takes as fact

whatever was said by Peer. Peer has never been a

legal owner of Génesis anywhere. This

being a material issue, Peer committed perjury and

Fuste passes Peer's fabrications as good

information.

Note: Peer claimed that it acquired the

rights to the song from PHAM, a Mexican music

publisher. The problem here is that whatever

assignment that GVL made to PHAM so that PHAM

would manage the song, assuming it was

legal, did not allow PHAM to pass any rights

(administration or otherwise) to others. So if

PHAM transferred rights to Peer the transfer is

invalid.

Also, the assignment of rights to PHAM

by GVL were also invalid, as the assignment

process did not comply with American copyright law

for transferring rights at another country. The

assignment was not not signed by any consular

officer or secretary of legation as was required.

This is what the law (Copyright Act of 1909) said:

Every assignment

of copyright executed in a foreign country shall

be acknowledged by the assignor before a

consular officer or secretary of legation of the

United States authorized by law to administer

oaths or perform notarial acts.

Fuste Opinion Page: 19

Fuste text: Peer attempted to obtain an

assignment from Plaintiffs for the song

Génesis

Error: In 1997 Peer attempeted to get an

assignment for all the songs which prior to

1997 Peer was claiming ownership. Then at a later

time (about 1999), Peer attempted to get an

assignment for Genesis only, but at the time Peer

was still refusing to cooperate with plaintiffs in

the search for the truth as to how it was that Peer

had acquired the various GVL songs it claimed to

own. With zero cooperation I don't think Peer wanted

an assignment. Just a defense for their case against

ACEMLA, where they were claiming ownership of the

song. Fuste likes to make Peer look good with his

comment.

Fuste Opinion Page: 19.

Fuste text: offering them an

administrative deal

Error: Same as above. No deal was ever

offered. They asked that I call them to discuss an

administrative but the "deal" was never presented.

Fuste likes to assume that Peer statements are

honest.

Note: The deal may have been illegal for

the PHAM renewal

songs if the PHAM assignments are covered by

Mexican law on the argument that Mexico laws has

no renewal periods and if PHAM still owned the

songs for the world minus PR, Peer could not be

working out "renewal" deals with plaintiffs, since

their license from PHAM was still in effect.

Note: At the time that Peer offered the

administrative deal (a better description is

"request of assignments) plaintiffs did not know

about renewals (except for having heard the word)

and when plaintiffs asked Peer about (in writing)

Peer did not reply. Peer did not even reply to a letter (see

below) that preceded the lawsuit from

plaintiff attorney Benicio Sanchez Rivera.

Note: Peer never notified plaintiffs

that renewal in their name had been made by Peer.

So only Peer knew they existed and that plaintiffs

had become owners of Genesis but plaintiffs did

not know it.

Very revealing of Fuste intentions:

Fuste did not mention the Peer request that

plaintiffs assign the songs to Peer in 1997

(see Fuste

comment) , an act that plaintiffs could do

only if plaintiffs were owners, a crucial

matter.

Fuste Opinion Page: 20

Fuste text: Peer did not notify Harry Fox

when its ownership claim in the 1 United States for

Génesis ended on December 31, 1997.

Error: Fuste fails to mention that they

also never notified heirs also and did all possible

to hide the fact.

Fuste Opinion Page: 20

Fuste text: BMG wrote to both Plaintiffs

and Peer informing them that BMG had received

conflicting claims

Fuste text: On March 26, 2002, Peer

contacted Harry Fox and requested that it stop

licensing the song Génesis on Peer’s behalf.

Error: Fuste fails to mention that Peer

did not respond to BMG or plaintiffs. This omission

makes Peer look less bad and shows bias by Judge

Fuste and helps Judge Fuste justify the low money

and absurd award of damages.

Fuste Opinion Page: 21

Fuste text: that permit them to broadcast

any song in ASCAP’s repertoire

Error: The statement is based on ignorance

as to how ASCAP operates. ASCAP does not give radio

stations a catalog of songs, so radio stations

operate blindly and are thus forced to play music

without knowing if they have the right to play the

song.

Fuste Opinion Page: 21

Fuste text: Not every song that Southern

Music registers with ASCAP will be listed on its

webpage; a song will be listed only if ASCAP has

surveyed or paid that song.

Error: This is fantasy land. Defies logic

since the only possible way a radio station (or

restaurant, etc.) could determine if they are

licensed to use a specific song in a reasonably

short time, it would be by finding the song listed

at ASCAP web page (the de facto catalog).... and

even that is questionable, since there is no

document possessed by the licensees to prove he was

authorized to play a particular song. Fuste gives

some credit to the ASCAP survey but the survey is

actually a sham that no one takes seriously.

No one sees or audits these surveys and no listener

doing a survey who hears a song during as survey can

reasonably identify songs unless they are on the

current hit list and that covers only a tiny part of

the music played on radio. For example in PR the

survey work is contracted to a firm that cannot be

identified because that is confidential (per ASCAP

manager in Puerto Rico, Ms. Santiago on television

interview).

Fuste Opinion Page: 21-18

Fuste text: Southern Music’s claim to the

songs Génesis and Apocalipsis in the United

States ended with the original term of copyright

Error: Wrong. Prior to plaintiffs, owner

was PHAM (per

copyright registration). If PHAM was owner at

renewal time is a mater of speculation, since that

GVL to PHAM assignment may have previously expired

due to Mexico law limitations on length of allowed

assignments. Per

Mexico

law, assignments cannot be perpetual as

in the US. The GVL assignment to PHAM has no express

provision for the duration of the assignment. Since

the contract has n time provision and the current

limit for duration is 5 years, it is possible that

PHAM rights on the songs ended many years ago,

perhaps in about 1975, if the law in affect was

identical to the current law for duration.

Mexico Law at present:

"Art. 33. In the absence of any express

provision, any transfer of economic rights shall

be deemed to be for a term of five

years. A term of more than 15 years may

only be agreed upon in exceptional cases where

dictated by the nature of the work or the scale of

the required investment."

Judge Fuste makes no mention of this

issue.

Fusté admits that the Peer 1997

assignment request was rejected, thereby

plaintiffs retaining ownership

Fuste Opinion Page: 22-1

Fuste text: The offers were not accepted

by Plaintiffs.

Error: Fuste doe not say that the 1997

assignment request offer $3.00 total (1 per

each of three groups of songs). That is not an

"offer".

In effect,

in 1997, an implicit agreement was reached between

Peer and the heirs: The songs rights belonged to the

heirs, regardless of what ocurred before that

moment.

Fuste Opinion Page: 22-15

Fuste text:: Southern Music

did not present evidence demonstrating the actual number

of songs it has registered with ASCAP. Tr. at 822:4-8

[Testimony of P. Jaegerman].

Error: Fuste did not ask why

such important evidence was omitted from the discovery

process.

See here for the Peemusic theory that

Plaintiffs had no right to information, something

that did not disturb the judge.

Fuste Opinion Page: 22-18

Fuste text: Peer first requested that

ASCAP stop licensing Génesis in the United

States

Error: Peer could only inform ASCAP that

they no longer owned the song and as such could not

give ASCAP such a command, where it only mentioned

the US, since that could be interpreted that Peer

still authorized ASCAP to allow it sub licensers to

continue licensing the song through the authority

received in the U.S. by a U.S. company. So the

statement of Fuste means that Fuste did not grasp

the meaning of Peer actions.

Fuste Opinion Page: 23

Fuste text: it is Peer’s practice to

contact the heirs to attempt to obtain an assignment

of the renewal term of copyright.

Error: Fuste should have added "without

telling heirs what is going on" or that the

songs entered a renewal term, as they did with GVL

heirs.

Fuste Opinion Page: 24

Fuste text: Peer granted Disco Hit a

“blanket” license

Error: No such license was ever granted to

Disco Hit. A non-transferable license issued by

Peermusic to a company named Aponte Distributors and

was issued in 1989 and Disco Hit commenced operation

in 1994 and has never receive a license for any GVL

song.

Error: Fuste fails to mention that such a

blanket license may be worthless because blanket

licenses do not mention specific songs. Fuste also

fails to mention that Peer had the opportunity to

clarify their alleged non existent licensing to

Disco Hit and remained silent. That silence in part

provoked this lawsuit and if it was not for the

lawsuit plaintiffs would know nothing about the Peer

license to Disco Hit. Also no license was ever

issued to Disco Hit

Error: Because of the judge's disparate decision, Disco

Hit continues to infringr the rights of plaintiffs. Both

Disco Hit and Peer are fully aware that they continue to

infringe the rights of heirs. See sample

here, of a CD purchased on 3-20-05 at a Walgreen

pharmacy. The infringed song (Borre tu amor) was taken

by Peermusic from Guillermo Venegas first and now from

his heirs. And the judge decided not to put a

stop to the thievery.

Fuste Opinion Page: 24

Fuste text: The songs Borré tu amor

and Mi cabaña appeared in Peer’s catalog,

though Peer admits that these songs do not belong to

it.

Error: The Fuste text means that these

songs were in fact infringed, but no such decision

was made and thus no damages were awarded. These

songs are in Disco Hit recording, Fuste said Disco

Hit got a blanket (has no song names) license from

Peer and disco Hit said they paid Peer for the

recordings. We repeat, Fuste decided that that there

is no infringement and damages were not awarded for

the ilegal use of these songs. Fuste contradicts

himself. Also no

license was ever issued to Disco Hit.

Fuste Opinion Page: 24

Fuste text: None of the other above-listed

songs, however, are identified on the blanket

license from Peer to Disco Hit

Error: A license is blanket when it does

not name songs. So the comment that none of the

songs are identified is nonsense. Also no license was ever

issued to Disco Hit.

Fuste Opinion Page: 24-20

Fuste text: The songs

Borré tu amor and Mi cabaña appeared

in Peer's catalog, though Peer admits that these

songs do not belong to it.

Error: Clearly these are two stolen songs.

Peer stole the songs from GVL "without the author

suspecting" and put it in their catalog. The judge

erred in not taking this into account in his

decision not to rescind the other highly

questionable "without the author suspecting"

songs and in his absurd award of $5,000 in

damages against Peermusic.

Fuste Opinion Page: 25

Fuste text: However, Peer stopped issuing

royalty reports in 1993 and did not provide any such

royalty reports to Plaintiffs until discovery in

this litigation.

Error: Fuste never says if this is right

or wrong and that helps Peer.

Error: Peer never proved it had sent any

royalty reports or royalty payments at any time

prior to 1993.

Fuste Opinion Page: 26

Fuste text: However, the ACEMLA

performance blanket license does not specifically

mention any song.

Error: But Fuste did not say the same

thing of ASCAP. Bias to help Peer look less bad.

Fuste Opinion Page: 26

Fuste text: Defendant Chávez-Butler

assigned all her copyrights to LAMCO on October 16,

1996.

Error: Fuste fails to mention that she had

no copyrights and she could not have assigned any

copyrights to LAMCO, making the transaction an

illegal one. This makes the estate-executor and

ACEMLA look less bad.

Fuste Opinion Page:

Fuste text: The licenses allowed the radio

stations to perform any of the songs owned by LAMCO.

However, the ACEMLA performance blanket license does

not specifically mention any song. Instead, a

brochure list of composers affiliated with ACEMLA

was provided to the various broadcasters.

Error: Fuste in nonchalant (marked by lack

of concern) about this method of fraudulent

operation by ACEMLA.

Fuste Opinion Page: 26- 4

Fuste text: Defendant Chávez-Butler

assigned all her copyrights to LAMCO on October 16,

1996..

Errors:

1. On 1-28-00 a Puerto Rico court

(Appeals) decided that if Chavez had any rights, she

ceded those rights to the Venegas children through a

signed agreement. She appealed, claiming that with

that decision she would loose her rigths to renewal

period songs. Yhe appeal was rejected.

2. Fuste dos not mention anywhere in

his decision that Chávez-Butler did not have

any rights at the time, as decided by the Puerto

Rico courts..

Fuste Opinion Page: 26

Fuste text: The total performance

royalties paid to ACEMLA were $260,432; however,

this included Génesis and the entire ACEMLA

catalog from the period of 1993-1998.

Error: Absurd proposition. Only six songs

had been used during the 1993-1008 period, so the

payment was for the six used songs only.

Fuste Opinion Page: 26-15

Fuste text: LAMCO and ACEMLA issued a

retroactive license to Banco Popular de Puerto Rico

(“BPPR”) on November 6, 1998. This license included

a mechanical license for Génesis for BPPR’s

Christmas Special CD and

video.

Error: Fuste says elsewhere

(75-4) that plaintiffs did not show that the song

Genesis was actually performed on the BPPR’s

Christmas Special. This anomaly of Fuste

justified his omission in awarding an additional

$43,000 r more, (depending on the deductible

expenses related to the $260,000 payment of BPPR)

in damages to plaintiffs.

Fuste Opinion Page: 26

Fuste text: LAMCO issued a mechanical

license to Sonolux for the songs Desde que te

marchaste and No me digas cobarde.

Error: The records (CD's) were by Sonolux

and ACEMLA was paid $67,912 in royalties to ACEMLA,

The amount paid to ACEMLA means that about 1,000,000

records were manufactured by an illegal

authorization (as determined by Fuste himself) of

ACEMLA and in the end Fuste did not find any

infringement by ACEMLA. As a result, had the

obvious infringement been seen by the judge

an award of $300,000 ($150,000 x 2 songs) should

have been made to plaintiffs. The maximum stipulated

in the law ($150,000) per infringed song should have

been awarded because along with the infringement

there was theft of ownership of the rights (the

stoten songs were copyright registered by LAMCO as

their own) and it was not mere usage.

A total disregard by Fuste of plaintiff's right to a

proper damage award.

More

about this crass error.

Fuste Opinion Page: 27-1

Fuste text: Thus, for the mechanical and

performance licenses together, LAMCO 1

Parties received $59,768.83.

Error: But Fuste contradicts himself by

saying elsewhere that the license was for the entire

ACEMLA catalog and omits any damages for the

"performance" infringement.

Fuste Opinion Page: 27-1

Fuste text: Sonolux paid a total of

$67,912.92 to LAMCO for this license; however, these

moneys subsequently were reimbursed to Sony/Sonolux.

Error: And the returning of the money made

the infringement all right? Absurd. The records

(CD's) were made by Sonolux and ACEMLA was paid

$67,912 (page 27-1) in royalties to ACEMLA, The

amount paid to ACEMLA means that about 1,000,000

records were manufactured by an illegal

authorization (as determined by Fuste himself) of

ACEMLA and in the end Fuste did not find any

infringement by ACEMLA.

Error: Fuste (nor anyone else) ever

inquired as to why no share of the royalties

was ever paid to the Venegas plaintiffs, if ACEMLA

claimed to own own the songs because Chavez assigned

her alleged partial rights to her (this is what

ACEMLA told Sonolux) or if GVL had assigned the

rights to ACEMLA when alive (this is what

ACEMLA claimed in court, as part of their switching

argument tactics).

Error: No sanction was ever imposed to

ACEMLA for lying to the court that GVL assigned

rights to them when in fact they were claiming to

Sonolux that they acquired their alleged rights from

Chavez..

Fuste Opinion Page: 27-3

Fuste text: Specifically, Sonolux deducted

the same sum from other royalties due and payable to

LAMCO. 1. Songs in Original Term LAMCO registered

the following songs not in their renewal term: (1)

Desde que te marchaste, (LAMCO’s Registration PA

948- 669, 3/19/99)

Error: This and all the ACEMLA

registrations may constitute criminal infringement

and Fuste is nonchalant about it.

Fuste Opinion Page: 27-6

Fuste text: LAMCO registered the following

songs not in their renewal term

Error: LAMCO registered 80 songs (

not 11 as stated by Fuste) a fact not

mentioned anywhere in the judge's opinion.

Note:

Whatever copies of the songs were included by

ACEMLA-LAMCO in their copyright registration

filings constituted infringement of owner rights

because the copies were not authorized by the

owners of the rights, the plaintiffs. This

infringement went unnoticed by the judge.

Fuste totally ignored the violation of

plaintiff's right to be the sole registrants of

the songs they own.

Fuste Opinion Page:

27- 29

Fuste text: LAMCO’s claim of ownership

depends upon a document signed by GVL during his

lifetime, the legal effect of which is disputed by

the parties. 31

Error: Wrong. Lamco's primary claim to

ownership was an assignment from the

estate-executor. After that collapsed in court, the

so called GVL assignment was raised by LAMCO. The

explanation given by Fuste, while technically

correct, helps ACEMLA image. Fuste showed bias here.

Note: ACEMLA said in Peer vs, LAMCO

(Perez Gimenez) that the SPACEM songs were in it's

catalog by mistake. Some mistake!

Fuste Opinion Page: 27-29

Fuste text: LAMCO’s claim of ownership

depends upon a document signed by GVL during his

lifetime,

Error: While Fuste says the ACEMLA

document is not valid. he is otherwise nonchalant

about the attempt of robbery. Why doesn't Fuste say

that since ACEMLA copyrighted the works and

plaintiffs did not complained about it and the

document ACEMLA used was too old, it was too late to

reclaim the songs as he did the Peer situation. Why

the bias?

Fuste Opinion Page: 28-1

Fuste text: The document on which LAMCO

relies for its claim of ownership to eight songs

written by GVL states “I CERTIFY: Those works

detailed above belong to me, Guillermo Venegas

Lloveras.

Error: Fuste simply states that the fact

that ACEMLA's claim is not valid, he can leave it

there. But the ACEMLA tactic could be construed as

an attempted appropriation (criminal infringement:

appropriation - not using) and Fuste is nonchalant

about the appropriation and has not awarded anything

for infringement.

Fuste Opinion Page: 28-4

Fuste text: The document

is written on Defendant LAMCO’s letterhead

Error: Wrong. The document may not have

been written on LAMCO letterhead and it could easily

be be a forgery where the LAM letterhead was added.

The original was never shown to Fuste. Note: The

spacing of horizontal asterisks may suggest he

document is a forgery.

Fuste Opinion Page: 28-9

Fuste text: In 1999, LAMCO Parties

registered copyright claims for 140 songs in their

original term that were written by GVL.

Error: This is not true. If that was said

by anyone it is perjury. ACEMLA made copyrights

registration on 1-8-97 (PA-835-281 for 33

songs), 3-16-99 (PAu-2-400-743 for 11 songs

and 3-19-99 (PA-946-618, for 18 songs). If ACEMLA

registered 140 songs then there are copyright

registrations that plaintiffs know nothing about and

ACEMLA did not present all documents for discovery

(perjury?).

Error: Fuste is nonchalant about an

illegal appropriation.

Fuste Opinion Page: 28-15

Fuste text: LAMCO’s retroactive license

for performances by ACEMLA to BPPR in 1998

identified six songs, including Génesis, and

covered the years 1993 through 1998, for a total

amount of $260,432.

Error: But then he contradicts this by

saying the performance license was for all songs in

ACEMLA catalog simply because ACEMLA said so after

using an accounting gimmick so as not ta have to pay

any royalties.

Note: ACEMLA lawyer sent a motion to the

court after the trial ended on 2-17-04

and before the sentence was issued to argue that

the license to Banco Popular was for the entire

catalog. Caro's motion is clear.... Banco Popular

only used a few songs out of that catalog, a

catalog that is fictitious because it has never

been issued to licensees.

Note: Under ACEMLA own arguments ACEMLA

had only a factional ownership of the song

Genesis. In spite of this ACEMLA parties never

shared any of the song's income with plaintiffs.

It would also mean that in addition to sterling

song rights, ACEMLA stole the income of the songs

by keeping all the money. Strangely judge Fuste

makes no mention of this fact in his opinion and

gave no punishment. Any other judge would have

scolded and punished ACEMLA for their fraudulent

ways!

Fuste Opinion Page 28-15

Fuste text: LAMCO’s retroactive license

for performances by ACEMLA to BPPR 1998 identified

six songs, including Génesis, and covered the

years 1993 through 1998, for a total amount of

$260,432 in royalties (one sixth of which would be

approximately $43,405.36). Plaintiffs’ Exh. 176; Tr.

at 472:25 - 473:5 [Testimony of L. Raúl

Bernard].

Error: It is clear: Bernard said the

Banco Popular license is for 6 songs. But Fuste says

elsewhere that it was for the entire ACEMLA catalog.

Fuste contradicts himself. Since ACEMLA did not

deduct expenses, the entire amount of $260,432

should have been awarded to plaintiffs.

Error: Of this money, none was awarded to

plaintiffs because, the judge says, plaintiffs did

not prove that the song Génesis was actually

performed. Elsewhere the judge says that the song

was performed. So the judge contradicts himself so

as not to award this money.

Note: The size of the ACEMLA catalog was

never mentioned in the Fuste opinion, a strange

omission.

Fuste Opinion Page: 28-21

Fuste text: The retroactive mechanical

license from LAMCO to BPPR in 1998 for the song

Genesis was for a total amount of $16,363.47.

Plaintiffs’ Exh. 176; Tr. at 472:3-16 [Testimony of

L. Raúl Bernard]. Civil Nos. 01-1215 &

01-2186 (JAF). Thus, for the mechanical and

performance licenses together, LAMCO Parties

received $59,768.83.

Note: The above statement is a plaintiff

allegation, not a Fuste conclusion.

Error: But Fuste only gave plaintiffs an

damage (restitution is a better word) award of

$16,363.47 and nothing for the rest of the money.

Even under the theory that the money was for the

entire ACEMLA catalog, at least some or all of the

money that ACEMLA received for the performance

license (a total of ~$260,000 had to be awarded.

Plaintiffs may be due all the performance licenses

money because aCEMLA did not present that deductible

expenses.

Error: The payment of $16,363.47 made by

Banco Popular covered the sales of phonomechanical

products during a 17 month period, starting in

Januery 1994 to May 1995. But Banco Popular sold

phonomecanical products up to at least 2002, That is

abour at least 100 months. It means that the damage

award given by Judge Fuste covered only 17 percent

of the time period that Banco Popular was selling

recordings and had wrongly paid ACEMLA and not the

real song owners, the Venegas siblings. This invoice,

with

a stamped date of 1-8-06, strangely, was

prepared by ACEMLA some 9 months or more before

Chavez (illegally) assigned any rights to

ACEMLA.Strange indeed and this was not detected by

anyone during the trial, an even stranger fact.

Fuste Opinion Page: 29

Fuste text: Plaintiffs’ 9

claims of ownership were not adequately

pled in Plaintiffs’ original complaint and,

therefore, are untimely and prejudicial;

Error: But previous Peer refusals to show

whatever documents it had prevented the making of

proper arguments.

Very strange claim, a type of lie to the

court. After 1997, when Peer requested from

plaintiffs the assignment of all prior Peer

claimed songs, Peer stopped claiming ownership

rights, so therefore Peer knew that the rights

belonged to plaintiffs by virtue of their being

the heirs, by default, so the rights did not have

to be "pled".

Fuste Opinion Page: 29-9

Fuste text: Peer Defendants counter that:

(1) Plaintiffs’ claims of ownership were not

adequately pled in Plaintiffs’ complaint and,

therefore, are untimely and prejudicial; and (2)

Plaintiffs’ challenge to the validity of the

contracts entered into by GVL and Peer Defendants

are baseless.

Error: Fuste never said that these

arguments are themselves baseless since at best for

Peer, it was the court's responsibility to analyze

those challenges. The validity of the assignments is

an issue that needs to be decide if the 1997

assignment request from plaintiffs meant nothing in

terms of ownership (see Fuste comment)

. Fuste avoided mention of the 1997 assignment

request (see

Fuste comment) , an important issue in the

case, since after that assignment request plaintiffs

had no reason to question plaintiff's own

ownership. Also plaintiff's attorney, Benicio Sanchez Rivera

wrote a letter to Peer to resolve any pending

issues, and the letter was never replied to (Peer

has admitted receiving the letter).

The Peer allegation that "Plaintiffs’

claims of ownership were not adequately pled in

Plaintiffs’ complaint" is nonsense since

plaintiffs presented a copyright registration that

covered all the song for which plaintiffs claimed

ownership. The fact that there clear error and

double registrations in our copyright can be

traced to Peer failure to inform and the failure

of the copyright system when searches were made at

Copyright Office.

Fuste Opinion Page: 29

Fuste text: which cannot possibly be

granted at this juncture

Error: Fuste never mentions the fact that

Peer withheld important information from heirs prior

to the case and during the case so as to defeat Peer

arguments.

Fuste Opinion Page: 29-17

Fuste text: Peer Defendants aver that in

September 7, 2003, Plaintiffs included a host of

theories or claims against Peer Defendants’

ownership in their Pre-Trial Order that they did not

allude to in their complaint.

Error: Again Fuste forgets that in 1997 (see Fuste comment)

Peer asked for assignment to all songs from

Plaintiffs. That established that the owners were

plaintiffs. Therefor plaintiffs did not need any

theory to claim to be owner. The reason for

presenting

Fuste Opinion Page: 30

Fuste text: as long as amendments do not

unfairly surprise or prejudice the defendant

Error: Defendant Peer, better than

plaintiffs knew all along what they were

doing. The surprises that developed during the case

were our surprises, not Peer's.

Fuste Opinion Page: 30

Fuste text: they must always exhibit

awareness of the defendant's inalienable right to

know in advance the nature of the cause of action

being asserted against him.”

Error: How could Peer not know in

advance that plaintiffs could make additional claims

if they knew of their criminal and fraudulent acts

and not we.

Fuste Opinion Page: 31

Fuste text: have incidental power to hear

and decide claims of title which necessarily bear

upon the ultimate question of infringement

Error: Fuste ignored the presented

evidences and is totally biased towards Peer and

ACEMLA. Fuste makes no mention of document 1387 (below).

Fuste Opinion Page: 31

Fuste text: Contract law governs the

assignment of copyrights.

Error: But Fuste ignored that Peer

consistently violated its contract and that their

contracts are unjust (something for nothing).

Fuste Opinion Page 31-12

Fuste text: As such, in order to determine

the extent, if any, of the alleged copyright

infringement against Peer Defendants, we must first

consider the various ownership claims to the songs

here.

Error: Fuste then proceeded to ignore our

claim that in 1997 Peer, after refusing to show

proof of ownership other than a 1952 contract

without song names, requested an assignment (see Fuste comment)

from plaintiffs for the very songs it now claimed.

So the various claims were not considered and the

most important one was ignored to the point it is

not even mentioned by Fuste.

Fuste Opinion Page: 32

Fuste text: We find no reason to void the

choice of law Civil Nos. 01-1215 & 01-2186 (JAF)

-33-

provision in the 1952 Agreement, and find

that Peer Defendants meet the requirements of

Walborg. Accordingly, New York law applies to

Plaintiffs’ claims for rescission here.

Error: The choice of laws provision in the

contract is very prejudicial to local puertorican

composers who cannot file complaints in local courts

with spanish speaking lawyers. In Puerto Rico

the first item in the judges code of ethics is that

no injustice shall be allowed. Under this precept of

no injustice shall be allowed, no Puerto Rican judge

would make the decision that Fuste made, which would

oblige claimants to sue in new York. Yet Fuste says

his decision is based on PR jurisprudence.

Note: The New York statute of

limitations may not be applicable, because one of

the parties, ACEMLA claimed the all the same songs

(and still did during trial - see web page) and

ACEMLA parties never agreed to a New York law

stipulations or to any stipulation with

plaintiffs, who never signed any agreement with

ACEMLA.

See

RESCISSION THEORY AND ERRORS below

Fuste Opinion Page: 32

Fuste text: provided the chosen

jurisdiction has a substantial connection to the

contract

Error: But Peer is now a Los Angeles

company and plaintiffs are not in New York. Anyway

Fuste decided that there was no recession based.

Fuste Opinion Page: 32-9

Fuste text: Walborg Corp. v. Tribunal

Superior de Puerto Rico, 104 D.P.R. 184 (1975), sets

forth the law governing choice-of-law provisions in

Puerto Rico.

Error: Fuste did not apply New York law in

determining if:

a. The 1997 assignment proposal from

Peer (see

Fuste comment) constituted a de facto

statement that Peer considered plaintiffs owners of

the songs.

b. If document 1387

(below) constituted fraud or robbery and what

was NY statute of limitation for those acts.

c. If NY laws prohibited totally one

sided contracts and what is the statute of

limitation for rescinding such contracts. For

example if slavery is prohibited by law and a

contract creates a slavery it cannot be rescinded

because the contract is older than the statute of

limitations?

Note: The assignment request by Peer in

1997 (see Fuste

comment) is well documented on GVL Facts

presented to the court on 12-19-03 by plaintiffs.

Fuste Opinion Page: 31-16

Fuste text: Peer Defendants maintain that

courts in this district have routinely upheld the

validity of choice-of-law clauses and have applied

the parties' designated state law.

Error: But routinely does not equate to

always.

Fuste Opinion Page: 32-24

Fuste text: We find no reason to void the

choice of law Civil Nos. 01-1215 & 01-2186 (JAF)

-33- provision in the 1952 Agreement, and find that

Peer Defendants meet the requirements of Walborg.

Error: But the 1952 agreement expired and

songs are now claimed on the basis of a letter that

requires Peer signature and does not have it and is

clearly fraudulent.

Fuste Opinion Page: 33-2

Fuste text: Accordingly, New York law

applies to Plaintiffs’ claims for rescission here.

Error: But does one has to take another

case, for rescission only, to New York state court?

See

RESCISSION

THEORY AND ERRORS below

Fuste Opinion Page: 33-5

Fuste text: Peer Defendants claim that

Plaintiffs’ contract claims are barred under New

York’s applicable six-year statute of limitations.

Error: In 1997 (see Fuste comment)

Peermusic made plaintiffs an offer so plaintiffs

would assign Peer rights to all the song they now

claim and some they do not claim. If the rights to